A Post about and not about Indigenous Peoples in Canada and the U.S. Important as those peoples are, larger issues about how we deal with the past are embodied here.

I wish all the best to Native Americans! But I think that the American Historical Review–it’s about history, right?–is not looking seriously at their past.

*A line from Kabir Chibber, “Shady Past,” NY Times Magazine, April 7, 2024. Excellent article.

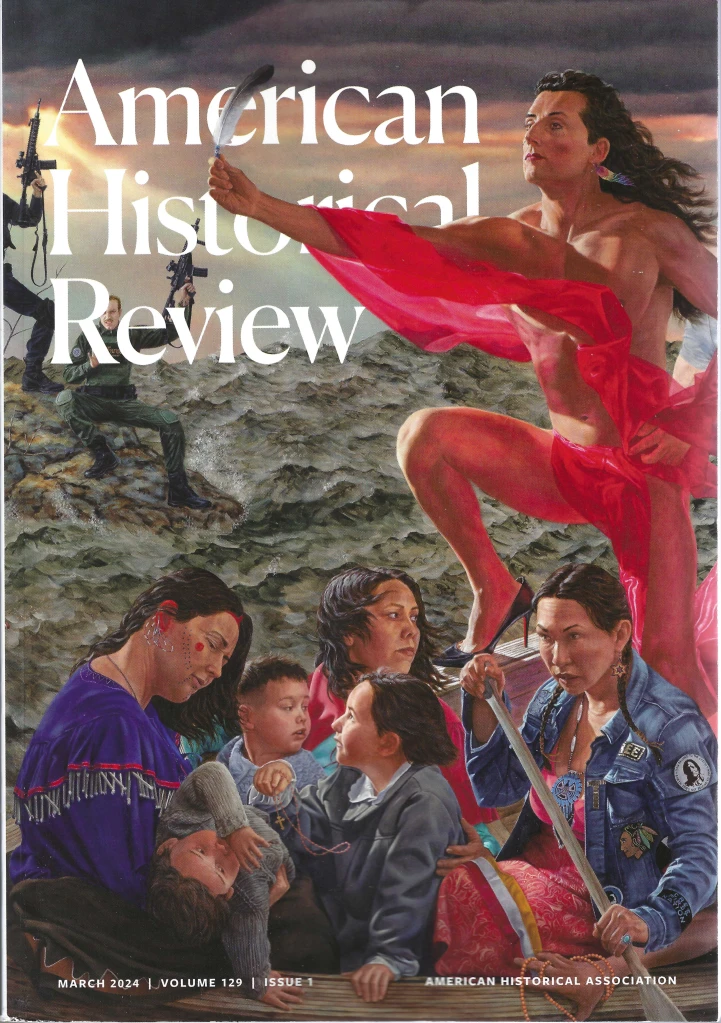

Cover of the American Historical Review March 2024. From a painting by Kent Monkman. Here’s the painting itself, now one of two by Monkman, a member of the Cree Nation, recently installed in the Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY City. This one is entitled “(Wooden Boat) Resurgence of the People,” done in 2019.

Inside the cover of the Am Hst Review is a bit about Monkman and the painting: “The March History Lab brings a new installment of Art as Historical Method that focuses on the place of history in art made by and about Indigenous peoples. . . . Monkman’s work explores issues of colonization, sexuality, and resilience [in order to challenge] received ideas about history and Indigenous peoples.

First, whose “received ideas”? this is bull; a substantial number of books and articles in recent decades have challenged old “received ideas,” which presumably refers to the old notion of Manifest Destiny, the brave pioneers, white heroes of the West, etc. All that has been gone for a long time.

“The self-identifying term used by the Cree is Ininiwuk , meaning men, or the original people.”

Many First Nations are known by names bestowed by others but call themselves “the people” or a variant of that idea in their own language. The best known example is the Navajo, whose word for themselves is Dineh, “the people.” The Ojibwe (Chippewa) name for themselves, Anishinaabe, means “the true people.” Other nations used the same vocabulary. This usage bestowed “superior status” on the ones who used it “and demeaned outsiders as lesser beings, sometimes less than human.”[ii] “Tribal history emphasizes one group of people who formed a political entity. Only in such a record does the language of the American Indians reflect their conviction and attitude that from their own tribe sprang the ‘true men’ and all others were strangers, that their folk heroes were giants while those of other tribes were pygmies.”[iii

Thus Monkman’s own nation, as well as his painting, starts with a problematic idea, one which contributed to violence between Indigenous groups. Many First Peoples, for instance the one called Navajo by outsiders, is Dineh,“the people,” in the nation’s own language. Others were not people; they were lesser beings. The Ojibwe (Chippewa) name for themselves, Anishinaabe means “the true people.” Other nations used the same vocabulary.[i] This vocabulary bestowed superior status” on the ones who used it “and demeaned outsiders as lesser beings, sometimes less than human.”[ii] “Tribal history emphasizes one group of people who formed a political entity. Only in such a record does the language of the American Indians reflect their conviction and attitude that from their own tribe sprang the ‘true men’and all others were strangers, that their folk heroes were giants while those of other tribes were pygmies.”[iii]

Not incidentally, to say that the Cree and other peoples were Algonquian speakers does not mean that they could communicate well with other Algonquian speakers. While not as broad a term as Indo-European languages, Algonquian covers the spoken tongues of peoples like the Cree, Ojibwa, Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Mi’kmaq (Micmac), Arapaho, and Fox-Sauk-Kickapoo. Iroquoian and Siouxan are other broad groups. Even if “dialect” is introduced, that doesn’t help much. There is the old q and a, “What’s the difference between a dialect and a language? A: a language has an army.”

Back to Monkman: “In the early 2000s, [Wikipedia] Monkman developed his gender-fluid alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle.” Get it? Mischief, Miss Chief, Testickle, testicle? We’re all on board with this, right? “Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is the two-spirit alter ego that Monkman uses as a fierce hunter, an artist, an activist, a seducer, a hero, and a performer.[30] She is also a mythological time traveler, existing during the creation of the world itself as well as in the ‘colonial spaces [of] the past and present.’” That’s Testickle with the red cloth, feather, and high heels near the bow of the boat. So the painting puts the queer (also a quite acceptable word now) world and the Indian world together to–um, I’m not sure why. Because they are not mainstream?

Let’s compare Monkman’s painting to a classic image of socialist realism.

Sergei Gerasimov, A Collective Farm Festival, 1937, Oil on canvas, 234×372 cm State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. The glorious future has arrived! Actually, the painting is about what will be. Ok, Gerasimov doesn’t do as well with individual faces as Monkman does. In a way, that’s the point: the people are a collective whose individuality shall be downplayed. Hey, that’s my take. No gender bending here, though!

The collective farmers are doing just fine. The boat people in Monkman’s work are not yet at the same wonderful future, but they are on their way to it. Thus in one painting, actually in almost everything I’ve seen by him, there are, first, Indians doing all right, thank you. Everyone on the boat is depicted as a human being, with distinct features. All are dedicated and determined. No pinched or haggard faces, no evidence of drunkenness or drug use, everyone looking good in “Survivance” and paddling happily to a fine future. Obviously they will get to some fine new existence. In the boat are children, even a baby. The future looks bright, if the boat can keep going through what looks like nasty water–perhaps it signifies the U.S. and Canada? We also get gender bending, as Miss Chief is the dominant figure.

Fine; anyone can renounce the past. That doesn’t change the past, or rather, renouncing it is a statement of defiance–now you are not going to tell us what to do or what to say. That attitude is a political statement, and should be seen as such. Nothing wrong with trying to be independent, except that American and Canadian Indians, as well as the Sami people of Norway, and so on, live in countries that with technology, laws, and traditions that affect Indians deeply and which they often make use of.

In Monkman’s painting, white Nazi-types with automatic weapons are having a good laugh–I think–it’s hard to tell from their small, undeveloped faces– from atop a rock in the water. Almost stick figures, these idiots appear to be celebrating something but are not smart enough to realize that they are stranded, their weapons doing them no good, and the boat with the resurgent people is leaving them behind–I suppose to die on their barren rock.

There is a Black man on the boat, who appears to be trying to pull a dead white man aboard. Another white man with a necktie flipped over his shoulder, a sure sign of evil, is holding onto a paddle of one Indian man. It’s not clear whether the white guy is trying to get on board or trying to hold back the paddling.

Why is the boat wooden? On it, there is no sign of any technology beyond paddling–the only tech in the picture is the useless guns of the whites. We are back to true nature, I suppose, when the Indians kept everything in balance and the buffalo gave themselves to the People to eat and make many other uses of. I.e., the folks in the boat are pure. Nonsense.

What is the connection (in my febrile mind) between the painting and the “Magical Multiracial Past?” In the piece by Kabir Chibber (neat that we have no idea if this is a male or a female, what ethnic origin, etc. Turns out, with a little research here, that he’s a male from India. Eh, so what), the subject of his article is the insertion of Black or other non-white persons into depictions of the past where such a figure was not present. The best example is the queen in the first year of Bridgerton, but this insertion is also in the latest version of Willy Wonka and in an adaptation of an Agatha Christie tale. We will see much more of it.

Chibber writes that in these imagined pasts, “every race exists, cheerfully and seemingly as equals in the same place at the same time History becomes an emoji, its flesh tone changing as needed.” But you can’t “get lost” in such presentations; something “is off.” “The tales are often boring, marked by a well-meaning blandness–by an avoidance of uncomfortable truths.” There is the danger of pretending “bad things didn’t happen.” That’s quite in the Monkman painting, where only one race has virtue.

I get that Chibber and Monkman are saying different things, but it seems to me that the same emphasis on dreamy boredom and desire to “correct” the past by goofing with it and inserting present values and images in it is common to both the Magical Multiracial Past (which criticizes all that) and the studious painting (endorses all that). Both images assert that the present overrides and triumphs over the past, with the winners being non-white because they hold on to their traditions. Yet I would say that the clothing of the Indians in the wooden boat is not “native” gear but is store-bought, or at least the cloth is, a pattern that began in the 17th century. What then is the past, and what might we draw–many things, many different attitudes and political outlooks, of course–from the past if we don’t insert the present into it?

It is right that America and Canada as states and as societies to work to boost people of color (but do keep in mind that membership in a tribe is a legal status, nothing more or less)–although I would much rather see efforts to help people who are suffering and/or are on the bottom levels of society.

Monkman’s work in this case is barely about the past–yet there the painting is on the cover of a historical journal, America’s leading one. And the painting hangs on the wall of America’s most prominent art museum.

The work is good but not great art, compared to much of the stuff inside the Met. Most of all, it is propaganda, a la socialist realist art of the 1930s and later.

Both the American Historical Review and the Met have let us all down.